In a nutshell: Never vote for politicians who accept big money from corporations or the rich.

We would all prefer politicians who answer only to the people, and not to wealthy special interests. Solving that is a tough problem; this article explains one aspect of it. As a scientist might put it, this element is necessary, but not sufficient to solve the problem.

What is that element? To put it simply:

Any politician who accepts big money from the rich, ends up serving the rich, instead of the people who elected them.

Politicians (especially the ones who love getting big donations from the rich) will claim that they’re not biased by those donations.

Give me a damn break. Rich people aren’t going to donate to a candidate if those donations aren’t going to do them any good. They want something in exchange: favorable laws, streamlined regulatory approval, or any of the other forms of legalized bribery that our system allows.

We’ve tried imposing rules on political donations from above, but the rich have so much money that they’ve essentially bought themselves immunity from those laws, mainly by way of pro-rich-people court decisions like Citizens United. We can’t stop rich people from, in effect, donating all the money they want to politicians.

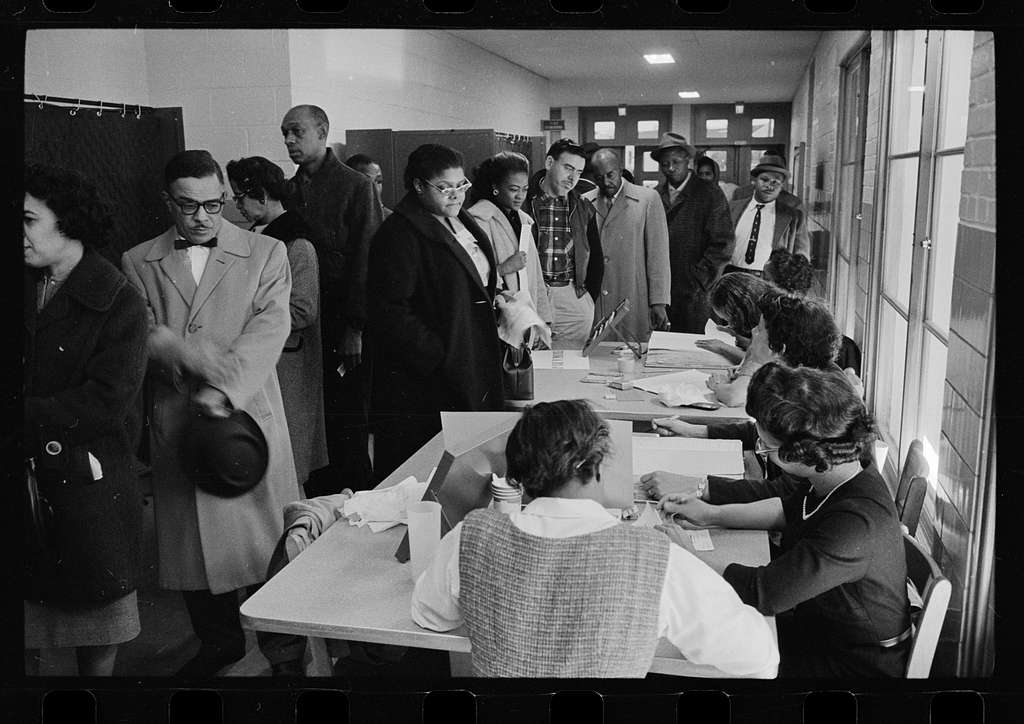

But we can stop politicians from accepting that money. More accurately, we can support politicians who refuse to accept that money. Organizations like the Richmond Progressive Alliance only support candidates that don’t take corporate money. Individual voters can be taught to follow this principle, and if enough of them do so, corporate politicians will have a harder and harder time getting elected.

What, no money?

Strictly speaking, a candidate could accept money from a corporation or rich person, as long as it’s not disproportionate. That means they won’t accept a donation that’s larger than what the average voter could manage. So a candidate might establish (for example) a $500 cap, and refuse any donations from any individual source over that amount.

A blue-collar family, if they really believed in a candidate, could probably scrape together that much to donate. A big company or rich family could easily do so. But since the cap is low enough so that any one donation doesn’t have a big impact on the campaign, the candidate is not beholden to the donor, regardless of whether they’re a single family or a billion-dollar company.

Obviously the cap needs to be small, and even smaller in very localized or small races; if your entire campaign budget is a few tens of thousands of dollars (say, for a city council campaign in a small town) then you might set a per-contributor cap of $100.

Whatever the number, the principle remains the same: do not let anyone have disproportionate influence on the candidate. This extends beyond just cash campaign donations; any kind of influence needs to be handled carefully. A corporation could get around the donation cap by giving money to a candidate’s church, or favorite charity. They could hold a benefit dinner and invite the candidate as a guest of honor.

There are countless ways the rich can use their wealth to manipulate people, and they are very good at doing it. No fixed set of rules can counteract people who do not want to play by the rules. Candidates—and voters—must be eternally vigilant about people with money and power trying to buy influence.

What about competing corporate candidates?

Here’s the monkey wrench: Say you’ve got a local race, with one corporate-free candidate and one corporate-backed candidate. Because the corporate-backed candidate has no compunctions about being a minion of the rich, they’ll happily take all the money and influence the corporation will give them. And because of that, they can probably out-earn and out-spend the corporate-free candidate.

This is why the individual belief principle is so important. If a voter really believes that they should never vote for a corporate candidate, then it doesn’t matter how much money the corporate candidates spend: they will not get that person’s vote.

It won’t be easy. Everyone is susceptible to propaganda, and big money buys a lot of propaganda. Corporations and their candidates will try very hard to hide their associations with one another, or confuse voters with lies about who gets money from where.

And a given election might have dozens of races; it can take a lot of time for a voter to get up to speed on everyone who’s running, not just to find out if they’re corporate-free, but what their intended governing policies are.

This is why organization and training are so important. Communities of voters who understand these principles, and how important it is to know who you’re voting for and why, can go a long way toward breaking the power of corporate candidates.